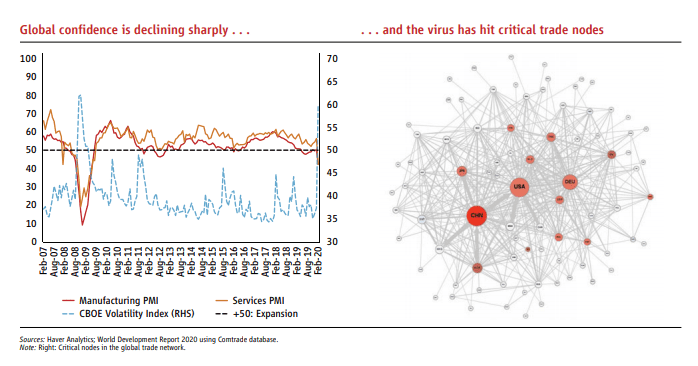

COVID-19 continues to take a humanitarian toll around the world, including in East Asia. Countries are rightly taking dramatic measures to slow it, and those measures have economic impacts. The COVID-19 virus that triggered a supply shock in China has now caused a global shock. Developing and major economies in East Asia, recovering from a trade war and struggling with a viral disease, now face the prospect of a global financial shock and recession.

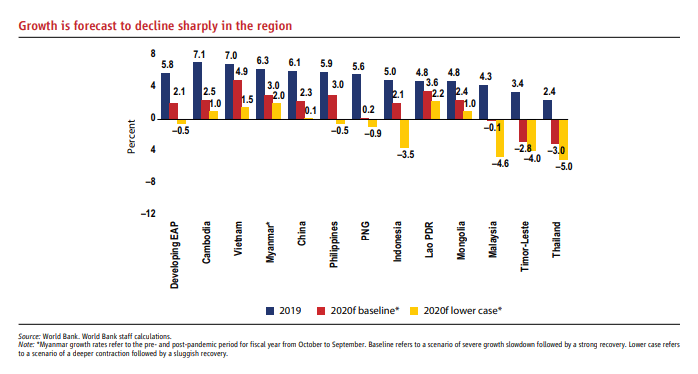

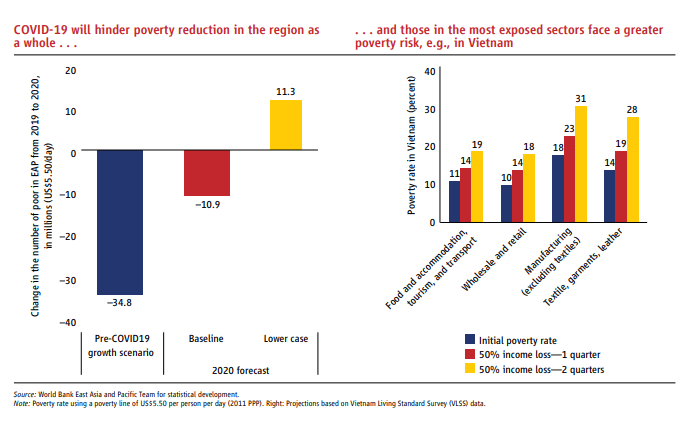

Several economies are expected to contract in 2020, which will lead to an increase in the poverty rate. Households linked to affected sectors are expected to suffer more. To deal with this crisis, countries need to act fast and decisively to contain the spread of infection, while expanding capacity both to treat people and to test and trace infections. Fiscal measures should provide social protection to cushion against shocks, especially for the most economically vulnerable.

Sound macroeconomic policies and prudent financial regulation have equipped most EAP countries to deal with normal tremors. Significant economic downturns seems unavoidable in all countries. Countries must take action now including urgent investments in healthcare capacity and targeted fiscal measures to mitigate some of the immediate impacts, according to East Asia and Pacific in the Time of COVID-19, the World Bank’s April 2020 Economic Update for East Asia and the Pacific.

“Countries in East Asia and the Pacific that were already coping with international trade tensions and the repercussions of the spread of COVID-19 in China are now faced with a global shock,” said Victoria Kwakwa, Vice President for East Asia and the Pacific at the World Bank. “The good news is that the region has strengths it can tap, but countries will have to act fast and at a scale not previously imagined.”

“In addition to bold national actions, deeper international cooperation is the most effective vaccine against this virulent threat. Countries in East Asia and the Pacific and elsewhere must fight this disease together, keep trade open and coordinate macroeconomic policy,” added Aaditya Mattoo, Chief Economist for East Asia and the Pacific at the World Bank.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, economic circumstances within countries and regions are fluid and change on a day-by-day basis. The analysis in the report is based on the latest country-level data available as of March 27.

In a rapidly changing environment, making precise growth projections is unusually difficult. Therefore, the report presents both a baseline and a lower case scenario. Growth in the developing EAP region is projected to slow to 2.1 percent in the baseline and to negative 0.5 in the lower case scenario in 2020, from an estimated 5.8 percent in 2019. Growth in China is projected to decline to 2.3 percent in the baseline and 0.1 percent in the lower case scenario in 2020, from 6.1 percent in 2019. Containment of the pandemic would allow for a sustained recovery in the region, although risks to the outlook from financial market stress would remain high.

Impact of COVID-19 in Asia: The Good And The Bad

Developing economies in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP), already struggling with international trade tensions and COVID-19, now face a global shock as the pandemic hits major economies around the world. EAP countries must act quickly, cooperatively, and at scale.

The negative effects of quarantine arrangements on labor supply could also be high depending on duration and sector. Manufacturing has been hit harder than service industries, where telecommuting and other technological aids limit the fall in productivity.

All these disruptions will lead to sharp declines in domestic demand. And their impact on economic growth will further propagate these disruptions. This compounding effect can magnify and extend short-run effects into the long run.

The Diplomat’s consulting service, briefly outlines “the good, the bad” of the COVID-19 fallout in the Asia-Pacific region. Below, our experts outline what you most need to know about the response from each government in East, Southeast, South, and Central Asia to the novel coronavirus.

China

The Good – The Chinese government moved swiftly to prevent the spread of the disease, instituting an unprecedented quarantine in Wuhan, where the disease was discovered. Through a combination of high-tech scanning and tracking of its population, coupled with strict controls on people’s ability to leave their homes, much less travel, China made progress. Amazingly, the epidemic is now under control. Data can be faked; the collapse of a health care system due to an overwhelming number of patients is much harder to cover up.

The Bad – As is now well-known, local and central authorities were not only slow to react to early reports of a mysterious new pneumonia-like illness in Wuhan, but even took steps to cover up the news. People issuing warnings on social media most famously Dr. Li Wenliang, who later died from what we now know as COVID-19 were rounded up and reprimanded by police. This let the pandemic spin out of control in the crucial early stages and arguably misled the rest of the world (including the WHO) into downplaying the severity of the problem.

Hong Kong

The Good – Hong Kong declared the new coronavirus an “emergency” in late January, and its efforts since have managed to ward off a spike in cases. The public clearly still remembers the lessons from SARS and reverted to mask-wearing and social distancing protocols more easily than many other populations. Schools were closed and public gatherings banned, but businesses, including restaurants, have been allowed to stay open, albeit with strict protocols in place on distancing between people.

The Bad – In the eyes of many Hong Kongers, however, that success came in spite of, not because of, the local government. As the rest of the world began to turn away travellers from China, the Hong Kong administration dragged its feet on instituting border controls with mainland China, to the consternation of medical professionals. Even in mid-March, when Hong Kong instituted mandatory two-week quarantines on all foreign travellers, the rules did not apply to mainland China.

Japan

The Good – Japan managed to avoid the worst of the first wave of infections, to such an extent that up until mid-March officials were still talking about holding the Tokyo Olympics as scheduled. As of April 1, Japan had only reported 2,500 cases and 60 deaths, many of those stemming from a single cruise ship. And that low number came despite businesses and borders remaining open at the time.

The Bad – Even as cases continued to climb in Tokyo, the central and local governments both declined to do much more than urge voluntary self-distancing practices – even after seeing the cautionary tales of lockdowns imposed too late in Italy and the United States. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe finally declared a state of emergency on April 7, but even that was mostly voluntary and fell short of a true lockdown, to the dismay of medical experts. Meanwhile, testing was limited, leading critics to say Japan likely had far more cases than its official count. Now infections seem to be surging and Japan may have to play the same painful game of catch-up seen in Europe and the United States.

Mongolia

The Good – Mongolia is as of this writing, at least another success story for COVID-19. The government reacted swiftly to news of the new virus, shutting its extensive border with China and closing schools and public gatherings back in early February. The government even cancelled the national holiday Tsagaan Sar, Mongolia’s lunar new year. So far, the strategy seems to have worked; Mongolia had reported just 30 cases of COVID-19 as of April 14.

The Bad – Mongolia’s health care system, like much of its social services, is starkly divided between urban and rural populations. According to the WHO, all of Mongolia’s specialized health care doctors are in Ulaanbaatar, where hospital facilities are more advanced. A largescale COVID-19 outbreak would easily overrun rural health care facilities, where Mongolia’s elderly are more likely to live.

North Korea

The Good – Pyongyang reacted very quickly, closing its border with China in January, before the new coronavirus had even been named. Those controls were later expanded to deny the entry of all foreigners. The swift response has been coupled by official rhetoric terming COVID-19 a threat to “national survival.” Clearly, North Korea is taking the disease seriously.

The Bad – There’s a reason Pyongyang is so concerned about the spread of the disease: its health care system is dilapidated and underfunded, lacking crucial medical supplies and medicine even under normal circumstances. It wouldn’t take much to overwhelm the North’s hospitals.

South Korea

The Good – South Korea is perhaps the poster child for managing a COVID-19 outbreak. A combination of extensive testing, location tracking, and contact tracing helped the country get control of the virus even after a massive surge in cases. Since then, countries around the world have been asking for advice and testing kits from South Korea, hoping to replicate its success.

The Bad – Though South Korea’s response in the past month has been exemplary, the initial explosion of cases shows the extreme danger of noncompliance with social distancing protocols. The outbreak in Daegu was linked to a fringe religious group, the Sincheonji Church of Jesus, that urged supporters not to wear masks and to continue joining mass religious services, with attendees in the thousands. After one churchgoer brought COVID-19 into the mix, the outbreak quickly spiraled. South Korea went from less than 30 cases on February 13 when Moon declared the outbreak nearly over to nearly 8,000 a month later.

Taiwan

The Good – Taiwan has been universally lauded as a model for its COVID-19 response, and for good reason: despite its close proximity to and frequent cross-border connections with China, where the outbreak began, Taiwan has limited its cases to just 393 as of April 14, with only six deaths. That’s because the government reacted quickly and decisively in January, by instituting early travel restrictions, rolling out testing, and asserting control of medical supply lines. Taiwan also recognized the potential for human-to-human transmission before China or the WHO did. Through these measures, Taiwan has been able to avoid the sort of sweeping lockdowns implemented around the world.

The Bad – Taiwan’s response has unfortunately left noncitizens out in the cold. First, the government controversially decided not to allow the children of Taiwanese-Chinese couples to evacuate to Taiwan in the early stages of the outbreak. Advocates have also raised the alarm over vulnerable migrant workers, many of whom are undocumented and may fall through the cracks of Taiwan’s COVID-19 prevention and treatment efforts.

Conclusion

The outbreak of COVID-19 is of course primarily a health and humanitarian emergency but understanding the potential economic implications of the pandemic is also crucial, for households, business and government. At the time of writing, the prevailing sense is one of uncertainty though, and so thinking about the economic outlook in terms of a range of possible assumptions or scenarios is even more important than ever. That said, our latest assessment is that the impact of COVID-19 is primarily a short-term one. Measures taken to contain the outbreak look to have stabilized its spread in China, and the challenge is to replicate that achievement in other economies. At the same time, supporting households and businesses in a period of much lower income should position economies to rebound once the immediate threat to public health has passed. Based on these key assumptions, we expect a short, sharp recession, followed by a rebound through late 2020 and into 2021. But the prevailing feeling is one of uncertainty.

Simon Pearson is an independent financial innovation, fintech, asset management, investment trading researcher and writer in the website blog simonpearson.net.

Simon Pearson is finishing his new book Financial Innovation 360. In this upcoming book, he describes the 360 impact of financial innovation and Fintech in the financial world. The book researches how the 4IR digital transformation revolution is changing the financial industry with mobile APP new payment solutions, AI chatbots and data learning, open APIs, blockchain digital assets new possibilities and 5G technologies among others. These technologies are changing the face of finance, trading and investment industries in building a new financial digital ID driven world of value.

Simon Pearson believes that as a result of the emerging innovation we will have increasing disruption and different velocities in financial services. Financial clubs and communities will lead the new emergent financial markets. The upcoming emergence of a financial ecosystem interlinked and divided at the same time by geopolitics will create increasing digital-driven value, new emerging community fintech club banks, stock exchanges creating elite ecosystems, trading houses having to become schools of investment and trading. Simon Pearson believes particular in continuous learning, education and close digital and offline clubs driving the world financial ecosystem and economy divided in increasing digital velocities and geopolitics/populism as at the same time the world population gets older and countries, central banks face the biggest challenge with the present and future of money and finance.

Simon Pearson has studied financial markets for over 20 years and is particularly interested in how to use research, education and digital innovation tools to increase value creation and preservation of wealth and at the same time create value. He trades and invests and loves to learn and look at trends and best ways to innovate in financial markets 360.

Simon Pearson is a prolific writer of articles and research for a variety of organisations including the hedgethink.com. He has a Medium profile, is on twitter https://twitter.com/simonpearson

Simon Pearson writing generally takes two forms – opinion pieces and research papers. His first book Financial Innovation 360 will come in 2020.