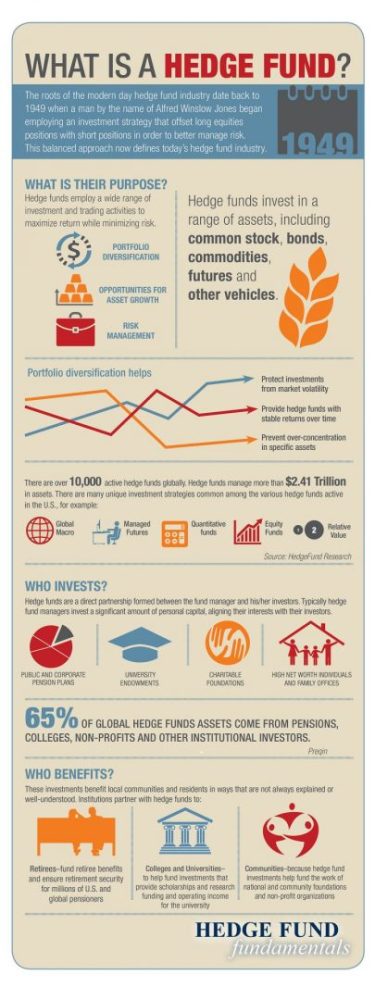

Hedge funds are essentially a very high-end type of pooled investment fund, similar in some ways to the mutual funds, unit trusts, and ETFs that most people’s pensions are invested in, but with a few notable differences. They have been around in one form or another since the late 1940s, but it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that they can truly be said to have infiltrated the public consciousness, with the high-profile successes of hedge funds such as Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates and George Soros’ Quantum Fund.

A Traditional Definition

The name ‘hedge fund’ refers to a type of investment strategy known as ‘hedging’. This involves trading two complimentary financial instruments at once, so that any potential losses from one investment will be, to a certain extent, offset by gains in the other. The financial instruments that can be used to this end include stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), forward contracts, insurance, options, swaps, futures contracts, and a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) and derivative products.

To give an example of a financial hedge, imagine that you have invested in the shares of an airline company such as Lufthansa or American Airlines. One of the biggest influences on the performance of an airline is the price of oil, which can be quite volatile at the best of times. If oil prices go up, margins are squeezed, and the company may need to raise ticket prices in order to make the numbers add up, which means less people will be able to afford to fly with that airline.

All in all, it’s bad news for the profits of the airline, so when oil prices spike, airline shares tend to fall in value. However, if you had also made some kind of investment in crude oil, such as shares in an oil company, or purchasing crude oil on a commodities exchange, then the value of that investment would probably rise as a result of the oil price increase. So, if the hedge worked, your oil investment would cancel out some or all of the losses on the airline investment, and you might even end up better off than you were before in terms of the capital value of your assets.

When two financial instruments compliment each other in this way, they are said to have a ‘negative correlation’, which means that when one asset rises in price, the other should fall, and has been seen to do so on many occasions in the past. Traders measure the strength of these correlations and work them into their equations when deciding how much to purchase of each asset in order to extract greater reward with less risk.

The Modern Hedge Fund

For many years, the term ‘hedge fund’ referred exclusively to funds that used hedging as the primary, or only, investment strategy. However, during the 1990s, hedge funds began to branch out into using other types of investment strategy such as credit arbitrage, fixed income, distressed debt, and quantitative trading. The industry has diversified to such an extent that some hedge funds don’t even use a hedging-based strategy at all.

Basically, ‘hedge fund’ has become a catch-all term for a variety of pooled investment vehicles administered by professional management firms, and they are usually structured as a limited liability company, a limited partnership, or something similar. Unlike mutual funds, they can’t be sold to the general public – they are only available to what the SEC describes as ‘accredited’ investors. To meet the SEC’s requirements, you need to be able to prove that you have a net worth of more than $1 million, which can be shared with a spouse, an income of over $200,000 per year over the past two years (or $300,000 between you and your spouse), and a reasonable expectation that your income will not drop over the next few years. Some hedge funds set the bar even higher than this.

The rules over accreditation mean that they don’t have to meet the same stringent regulatory and licensing requirements as retail funds, which gives the fund managers far greater flexibility with regards to how they achieve returns. In many cases, this means that they significantly outperform retail investments such as mutual funds – although the bar for entry is much higher. Basically, you need to have quite a lot of money to begin with if you want to invest in a hedge fund, and you need to be able to prove it.

Hedge funds are by far the most popular high-end investment product, but they are not the only one. For example, private equity funds share some attributes with hedge funds, but they differ in terms of the types of strategies used and the entry requirements. After undergoing rapid expansion in the 1980s and 90s, the hedge fund industry continued to grow in the 2000s, and in June 2013 the total recorded value of assets held in hedge funds reached an all-time high of $2.4 trillion.

The goal of most hedge fund strategies is to achieve what is known as an ‘absolute return’ – which means making money from the markets whether they are rising or falling. In order to make sure there is no conflict of interest between the fund manager and the investors in a hedge fund, it is common practice for fund managers to invest their own money in the fund. This ensures that their interests are aligned with those of the other investors, and helps to establish trust among the investors in the fund.

The value of a hedge fund is directly related to the value of the assets under management in the fund. This means that it increases and decreases in tandem with the value of the assets that are held in it at any one time. The amount that the investor can later withdraw is related to the net asset value of the fund – which is the value of the assets in the fund minus the fund expenses, which are usually calculated annually. A typical management fee might be 1% of the assets of the fund, with a performance fee on top of that such as 15% of the increase in the fund’s net asset value over the course of the year.

If you want further clarification as to how a hedge fund works, there is quite a good explanation in the following video from Marketplace.com:

A Changing Landscape

While hedge funds are exempt from many of the regulations associated with retail investment, regulators in the US and Europe introduced legislation in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 to tighten up the regulation of hedge funds, giving government agencies greater oversight and plugging some of the gaps in regulation between retail investment and hedge funds. However, the structures used for hedge funds ensure that fund managers still have a lot more flexibility about how they invest than they might if they were managing a mutual fund, for example.

At present, the biggest hedge fund in the world is Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates, a US firm based in Stamford, Connecticut with around $150 billion in assets under management as of 2013. Other major players include the UK-based Man Group, with $52 billion under management, Brevan Howard with $40 billion, and Paulson & Co with $18 billion.

Despite the increases in regulation, and the industry as a whole suffering as a result of the financial crisis, the industry continues to grow and has fully rebounded from its pre-crisis peak. Obviously, the industry performs better during boom times, and many hedge funds have had a bit of a bumpy ride in recent times, hedge funds remain one of the most effective vehicles for wealth protection and capital growth over the long term.

Read More:

I am a writer based in London, specialising in finance, trading, investment, and forex. Aside from the articles and content I write for IntelligentHQ, I also write for euroinvestor.com, and I have also written educational trading and investment guides for various websites including tradingquarter.com. Before specialising in finance, I worked as a writer for various digital marketing firms, specialising in online SEO-friendly content. I grew up in Aberdeen, Scotland, and I have an MA in English Literature from the University of Glasgow and I am a lead musician in a band. You can find me on twitter @pmilne100.