“Extraordinary times require extraordinary action. There are no limits to our commitment to the euro. We are determined to use the full potential of our tools, within our mandate.” Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically affected global economic activity since early 2020. The coronavirus (COVID-19) is significantly impacting the financial markets. Measures are being taken at a national and European level to ensure that member states are functioning orderly. The severity of these measures has begun to ease in some jurisdictions, as authorities are proceeding to gradually lift lock down measures and reopen certain sectors of their economies. These measures affect businesses, financial institutions and their ongoing regulatory requirements. Nevertheless, there could still be a prolonged period of social distancing and other containment measures in force which will have a profound effect on all areas of the economy especially those that have or by their nature, are personally interactive.

At the start of their coronavirus lockdowns, European governments scrambled to shore up businesses and the public sector with subsidies in a bid to ensure that a post-virus recession is not that prolonged because of a resulting cascade of layoffs and bankruptcies.

As the COVID-19 health crisis appears to be slowly passing its most critical phase, European leaders and finance ministers are increasingly focused on questions of how to pay for the crisis to restart the economies of the eurozone and of the European Union once the storm has passed.

But the economic prospects look bleak for Europe with the impact of the lockdowns, now being slowly relaxed, lasting many years, analysts say. Governments, saddled with annual deficits at war time levels, face dismal choices between cutting public spending or increasing taxes either of which would slow down the recovery.

As of late May, European countries have further eased coronavirus restrictions and allowed for the opening up of more businesses, including bars and hair salons, following two months of economically crippling shutdowns.

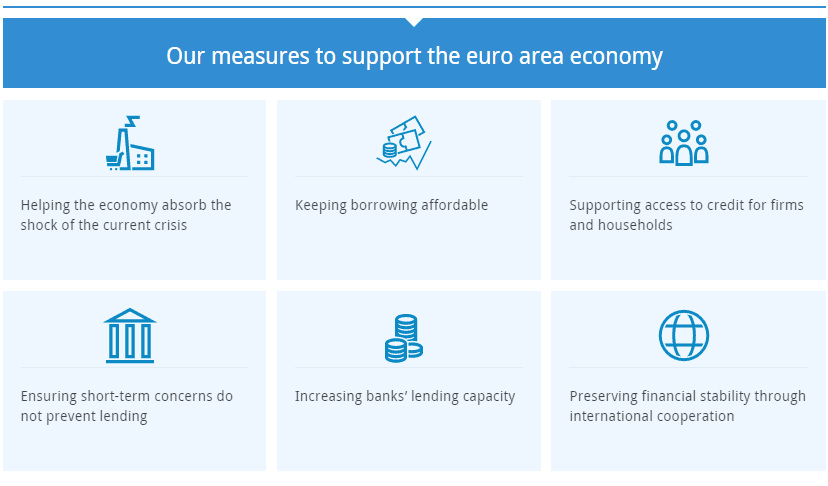

ECB’s measures and financial stability program

The European Central Bank’s response to the coronavirus has calmed markets while setting it on a path that could test its commitment to the mission to keep prices stable. Despite serious initial hesitations, the European Central Bank (ECB) has shown aggressive creativity in leading the immediate crisis response. Nevertheless, disagreement has emerged over the most suitable instruments to address the post-crisis economic recovery, with some countries pushing for the issuance of so called “corona-bonds,” a proposed Eurobond that would provide liquidity to countries whose economies are most in need of post-pandemic support, while mutualising risk across all eurozone members.

Earlier this month, Eurogroup finance ministers agreed to a series of measures intended to help countries address the crisis and begin to recover, but failed to agree on long-term economic recovery tools. With governments struggling to agree on joint fiscal action, ECB President Christine Lagarde and her colleagues have ramped up bond-buying of vulnerable nations, soothing investor concerns over the cost of fighting the pandemic.

That strategy compensates for the euro zone’s lack of a fiscal union or jointly issued bonds, by effectively mutualising debt via the central bank. It prevents borrowing costs in highly indebted nations such as Italy from spiralling out of control. The ECB will have to consider withdrawing stimulus even if weaker economies can’t afford higher debt repayments, potentially sparking another crisis.

“The ECB finds itself ever more politicised, as the asset purchases increasingly blur the lines between fiscal and monetary policy,” said Anatoli Annenkov, an economist at Societe Generale in London.

Originally, the ECB had a slow start in responding, marked by a verbal faux pas of Christine Lagarde, who said that it was not the central bank’s job to “close spreads” in sovereign bond markets. A spread is the difference in yields between two bonds from different eurozone governments. This led to the worst-ever one-day decline in Italian bond prices. The central bank’s crisis approach has so far been validated by financial markets, easing pressure on Italian bonds.

But since then, the ECB has launched a lot of measures to help stabilize the European economy and committed to do “whatever it takes” to sustain the eurozone. First, it launched a new Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program, offering up to 750 billion euros until the end of 2020. This means the ECB will buy national debts, including debt from Greece, which previously was excluded from the buying program because of its low credit rating. In addition, the ECB added an extra 120 billion euros to its existing asset buying program, which is called the Public Sector Purchase Program.

So, the ECB buys bonds of governments but also bonds issued by corporates. By buying government and corporate bonds, the ECB lowers interest rates, helping governments and firms to borrow cheaper and invest, which will create jobs and stimulate economic growth. The ECB has also provided cheap loans to commercial banks because it wants those banks to lend to small and medium sized firms. Through all these programs, the ECB will buy over 1 trillion euros’ worth of bonds this year and provide loans at very low interest rates.

Corona-Bonds

The concept of Eurobonds had been previously raised in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and was considered by the European Council at various crisis meetings as a means to further European integration through advancing plans for a deeper fiscal and banking union. But the more “virtuous” countries, of northern Europe, opposed those proposals and they argued against sharing risk with perceived less virtuous countries which already had higher debt stock than contemplated by strict EU fiscal rules. Now, given that the spread of the virus cannot be fairly blamed on any individual EU country, the issue of Eurobonds (called “corona-bonds” to make it clear why they would be needed) has reopened the earlier divide.

The corona-bond proposal continues to be rejected by enough countries and therefore, its prospects appear poor. Still, the concept of risk-sharing is not entirely dead. The Eurogroup has tentatively recommended the consideration of a French-designed “Recovery Fund” that could provide significant financial support for future economic recovery of the most affected member states in a size commensurate with the extraordinary costs of the current crisis.

The ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme

Here is where the ECB comes in. The really distinctive feature of the new programme of asset purchases, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), is that the ECB has publicly announced it is ready to exercise the utmost flexibility in the geographic distribution of its purchases; it is no longer bound by the principle of proportionality to the capital key of each country. The ECB is adamant in distinguishing between two cases: it will not do anything that smacks of ex-post monetary financing of reckless deficits; but it will do whatever it takes to prevent a crisis hitting a responsible government from threatening the integrity of the euro area.

Still, this is not a fireproof solution. The PEPP is set to expire at the end of 2020; however, it is easy to envisage that it will be renewed, particularly if the need emerges. It might also be unwise to put too much pressure on the ECB as the saviour of last resort. The ECB is rightly proud of its image of independence and would do nothing that could jeopardise a reputation earned from 20 years of operations, all the more so if publicly it is put under pressure by politicians.

Challenges to Overcome

Well, the EU has struggled to produce a coordinated response to the crisis, which represents the latest stress test to the solidarity of the bloc. The future of the European project may depend on how EU leaders handle this crisis. It is politically difficult to implement timely and comprehensive macroeconomic stabilisation in crises in the eurozone because its institutional framework is incomplete. That means the euro area lacks a centralised fiscal authority, a real European treasury. There is the ECB, a common monetary authority, but there is no common fiscal authority, or treasury. Also, the existing rescue tools, such as the European Stability Mechanism, a bailout fund established in 2012, is very restricted and conditional on adjustment measures to offer the adequate support to crisis-stricken countries.

Conclusion

What shape the recovery will ultimately take, remains highly uncertain at the current juncture, even as authorities gradually start to ease lockdown measures in some economies.

The ECB has responded forcefully to this historic crisis by adopting a wide-ranging set of carefully calibrated measures that collectively help mitigate the economic and financial fallout from the pandemic. Our measures contribute to easing financing conditions of firms and households and supporting banks in their effort to maintain viable liquidity conditions in the economy at large.

At the same time, other authorities will have to play their role as well, since ultimately the recovery will depend on the right combination of monetary policy and effective fiscal and regulatory policy, both at a national and at an European level.

Simon Pearson is an independent financial innovation, fintech, asset management, investment trading researcher and writer in the website blog simonpearson.net.

Simon Pearson is finishing his new book Financial Innovation 360. In this upcoming book, he describes the 360 impact of financial innovation and Fintech in the financial world. The book researches how the 4IR digital transformation revolution is changing the financial industry with mobile APP new payment solutions, AI chatbots and data learning, open APIs, blockchain digital assets new possibilities and 5G technologies among others. These technologies are changing the face of finance, trading and investment industries in building a new financial digital ID driven world of value.

Simon Pearson believes that as a result of the emerging innovation we will have increasing disruption and different velocities in financial services. Financial clubs and communities will lead the new emergent financial markets. The upcoming emergence of a financial ecosystem interlinked and divided at the same time by geopolitics will create increasing digital-driven value, new emerging community fintech club banks, stock exchanges creating elite ecosystems, trading houses having to become schools of investment and trading. Simon Pearson believes particular in continuous learning, education and close digital and offline clubs driving the world financial ecosystem and economy divided in increasing digital velocities and geopolitics/populism as at the same time the world population gets older and countries, central banks face the biggest challenge with the present and future of money and finance.

Simon Pearson has studied financial markets for over 20 years and is particularly interested in how to use research, education and digital innovation tools to increase value creation and preservation of wealth and at the same time create value. He trades and invests and loves to learn and look at trends and best ways to innovate in financial markets 360.

Simon Pearson is a prolific writer of articles and research for a variety of organisations including the hedgethink.com. He has a Medium profile, is on twitter https://twitter.com/simonpearson

Simon Pearson writing generally takes two forms – opinion pieces and research papers. His first book Financial Innovation 360 will come in 2020.