By Joshua Roberts, Associate Director at JCRA

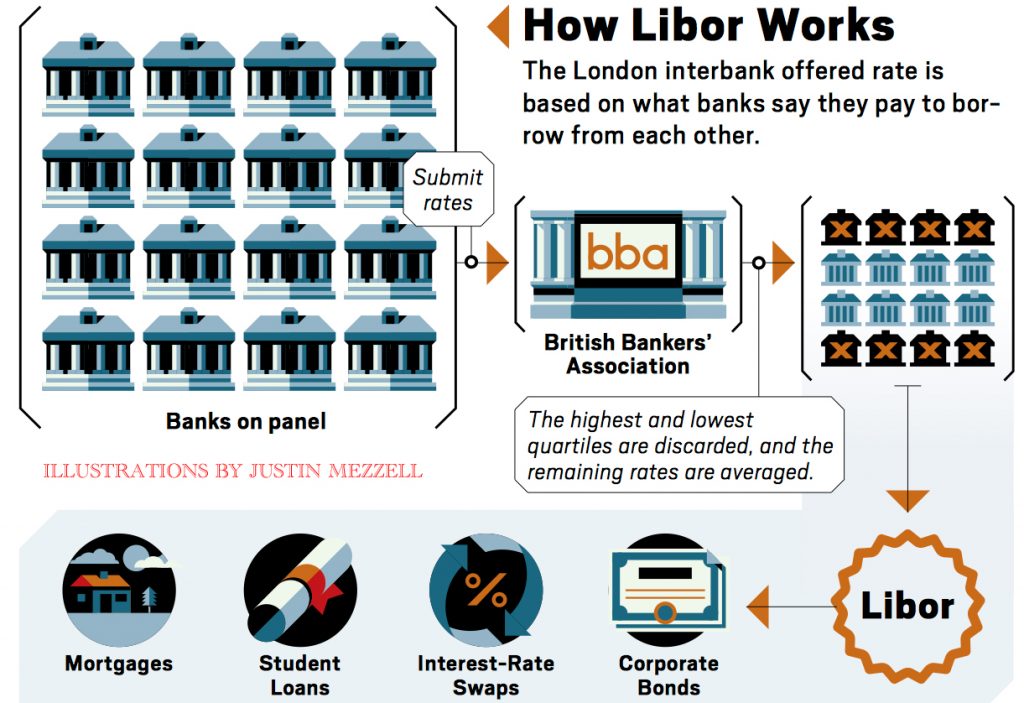

Regulators around the globe are attempting to steer markets away from the self-reported, manipulation-prone IBOR family towards benchmark rates based on actual market transactions. If financial supervisors get their way, most interbank rates will lose their regulatory support by the end of 2021.

It is an endeavour most market participants seem to agree with in principle, but good policies require more than just good intentions. For the replacement of LIBOR to be successful, policy makers will need to address a host of practical issues. Many of these are not adequately covered by current proposals.

One obvious set of problems relates to the replacement rate, SONIA, which is based on overnight lending rates. First, its derivative market is underdeveloped with regards to depth and breadth compared to LIBOR. Second, at present SONIA is published only as an overnight rate, rather than for a range of borrowing periods (1, 3, 6 months) as LIBOR is. Moreover, rates are only determined in arrears – not ideal if you are a corporate treasurer trying to plan your cash flows for the next quarter.

The real headache is not finding a suitable replacement rate that will be used going forward, but rather how to transition from the current regime to the new

While these are all valid concerns, they are likely to sort themselves out. The derivative market for overnight rates will keep expanding and eventually mature, offering a broad set of products for a full spectrum of tenors. Moreover, one would hope that fixings for standardised swap contracts will give rise to term rates that mimic those for LIBOR.

The real headache is not finding a suitable replacement rate that will be used going forward, but rather how to transition from the current regime to the new. It seems very likely that the change of a reference rate under a loan or derivative would produce a valuation impact. Does this imply that counterparties would have to compensate each other for the ensuing value transfer? If yes, how would these be determined and by whom? And how can this realistically be accomplished given the sheer number of affected contracts we are talking about?

One would hope that the legal arrangements governing affected contracts might provide guidance, yet a large number of affected contracts probably do not include language that caters for a permanent discontinuation of their benchmark rate. Various industry bodies are proposing alternative provisions that borrowers, lenders and derivative counterparties could agree to insert into their contracts. If these provisions are not economically neutral, however, finding a common position may be extremely difficult.

Moreover, current proposals by the LMA (loans) and ISDA (derivatives) for processes to determine a replacement rate do not appear to be as well-aligned as one would wish. Could borrowers therefore end up in a situation where the rate under a floating rate loan or bond no longer matches the associated hedging contracts?

All told, the discontinuation of LIBOR could turn out to be an administrative nightmare, with painful economic side effects, unless a unified view covering bonds, loans and derivative contracts alike emerged. Alas, that doesn’t seem to be the case at present.

There is widespread acknowledgement of the importance of this topic, dubbed “The risk that is bigger than Brexit” within the industry. As a result, it is only natural to ask what to do about it and how one should prepare. Yet when asked what concrete action points to take, most people – be it lawyers or bankers – shrug. A grandfathering of existing contracts based on LIBOR in conjunction with a gradual phase-out would be welcome, but it appears that this is not under consideration.

So here we are, stuck in limbo with a lot of questions and very few answers. In the meantime, all we can do is to keep bringing it up when loans are arranged, derivative contracts negotiated or in committees working on the discontinuation of IBOR. After all, not borrowing and not hedging is no solution either.

Read More:

best hedge fund managers of all time

best performing hedge funds 10 years

top 10 biggest hedge funds us 2024

richest hedge funds in the world

biggest hedge funds in san francisco

HedgeThink.com is the fund industry’s leading news, research and analysis source for individual and institutional accredited investors and professionals